History and Development of Upper Darby

Township Second Edition

Chapter 5 – The Four Hamlets of Upper Darby

by Thomas J. DiFilippo

The growth rate of the township changed about 1830 when textile making moved from the homes into mills. Before 1830, the spinning of yarn and the weaving of cloth was mostly performed at home by the women and primarily to satisfy the family’s needs. About 1830, some old grist mills were converted to spin yarn that was sold to individuals who wove their own crude cloth. About 1840, the mills became “integrated,” meaning they spun the yarn from raw material, then wove, finished and dyed the cloth. This was the beginning of a prosperous large textile industry in Upper Darby that lasted into the mid-1900s.What became this country’s massive textile industry began in New England then spread to the Delaware Valley. Philadelphia became a major textile center with many mills in Germantown, Manayunk, Kensington, and Blockley. Realizing the potential market for textiles, descendants of the Garretts, Sellers, and Levis, followed by the Burnleys. Kellys, Kents, and Wolfendens, built or converted to textile mills. This expansion occurred after the flood of 1843 because that event destroyed nearly everything along the creeks.Most of the mills employed Immigrants from England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and later Irish Catholics. Although the managers and skilled workers were male, the laborious jobs were performed mostly by women and children. The mills owned the nearby “mill houses” and rented them to their employees. Workers were expected to follow the politics of the mill owners. Very few owners had compassion for the workers and thus the working conditions were poor, the salaries meager and the working hours long. These conditions bred frequent labor disputes and were the cause of the early child labor laws and unionization.As the Upper Darby textile industry grew, so also did the areas of Kellyville (Oakview), Addingham, Cardington, and to a lesser degree GarrettsFord (Garrettford).

Charles Kelly

Charles Kelly was born in County Donegal. Ireland in 1803 and came to America in 1821. He was sponsored by an uncle, Denis Kelly who arrived in America in 1806 and established textile mills in Havertown (Note: Some historians report that they were unrelated.) Both were Catholics, ambitious, trained textile makers, and each became wealthy industrialists, owning mills in their respective areas. Both were responsible for community growth and for financing two of the earliest Catholic churches in Delaware County. The churches were named after their patron Saints; first in Havertown St. Denis, and then in 1849, St. Charles Borromeo in Upper Darby Township.

In 1826, Denis and Charles rented a cotton mill that Asher Lobb built in 1820. That mill was located beside the Darby Creek on Baltimore Pike. Shortly thereafter Denis sold his share of the business to Charles and concentrated his interest on operating his mills in Havertown. Charles’ mills became so successful that by 1841 Kelly was among the township’s most wealthy people. As his wealth grew, he purchased properties along Baltimore Pike and in the area of today’s St. Charles Church – Oakview.

Charles began building his community in 1840 when he purchased property from Thomas Rudolph and Hannah Hibberd. After the flood of 1843, he purchased the late Thomas Garrett’s mills, twenty-six acres, a mansion house, and nine tenements. In 1845 he purchased property from Judith Flounders, Moses Wells, William Lobb, and Asher Lobb. In 1846 he bought property from Catherine Lobb and Abraham Rudolph. By 1851 he owned forty-one tenements that he rented to his employees. Between 1853 and his death in 1864, he made additional purchases from William Towne, Nathan Browne, Henry Hay, Samuel Harrison, and John Wall. Dr. Smith, in his 1862 book, mentions that Kellyville extended about one mile up the Darby Creek from Baltimore Pike.

Soon after purchasing the mills, he expanded their capacity and increased the number of workers. In 1826 Kelly’s mill was described as a stone cotton factory, 72 x 42 feet and four stories high containing 30 carding engines of 24 inches, five drawing frames of three double heads each, four double speeders of 20 spindles each, one speeder of ten spindles, one stretcher of 90 spindles, one warping machine and dresser, 32 power looms. 1,260 thresher spindles, 1,776 mule spindles, all producing about 3,300 pounds of cotton per week. It employed about 11 men and 70 women, girls and boys and had houses for sixteen families.

A typical employee worked a twelve hour day, six days weekly and received meager wages. A typical supervisor received $48 per month. A skilled worker received $14 to $18 monthly whereas a laborer received between $6 and $10. Women were usually paid less than the men for similar jobs. It was common for whole families-husband, wife and children – to work in the same mill. The combined year’s earnings of a father, mother and one child amounted to approximately $350. Typical rent for a better tenement house was $25 per year or approximately $2 per month. A typical worker paid $.50 to $1.00 in yearly taxes.

On November 5, 1847, a writer from the Delaware County Republican Paper toured the Kellyville factory and reported this description. He met Charles Kelly who was the superintendent of the Denis & Charles Kelly Mills. “The mill is 160’x 52’, five stories high, clean, well ventilated, a high quality mill of mostly new machinery. The mill is driven by two water wheels 15’ In diameter by 16’ wide, assisted by a high pressure steam engine of fifty horsepower. Two hundred operatives work in the mill, producing 35,000 yards of ticking, flannel, and pantalone per week. They use 40,000 pounds of cotton per month. The workers are happy and contented. There are three other buildings plus a Sunday School, fifty dwellings for workers and others being built. A new 500’ dam is being built. The population of Kellyville is about 500.”

By 1851, Kelly Mills employed 200 people producing ticking, canton flannel, and other cloths. Kelly attracted many Irish Catholics who came to Philadelphia between 1830 and 1850 to escape English persecution and famine. He was able to attract the Irish Catholics from Philadelphia because of their problems that began in the 1830s. Considerable resentment existed between the Protestants and Catholics when the Catholics attempted to use their version of the Bible for their children in public schools. The conflict culminated in the 1844 bloody riots. Some historians believe the riots were more ethnic than religious because the German Catholics were not treated the same. They concluded that the resentment was English Protestants against the Irish.

In 1826, Denis and Charles rented a cotton mill that Asher Lobb built in 1820. That mill was located beside the Darby Creek on Baltimore Pike. Shortly thereafter Denis sold his share of the business to Charles and concentrated his interest on operating his mills in Havertown. Charles’ mills became so successful that by 1841 Kelly was among the township’s most wealthy people. As his wealth grew, he purchased properties along Baltimore Pike and in the area of today’s St. Charles Church – Oakview.

Charles began building his community in 1840 when he purchased property from Thomas Rudolph and Hannah Hibberd. After the flood of 1843, he purchased the late Thomas Garrett’s mills, twenty-six acres, a mansion house, and nine tenements. In 1845 he purchased property from Judith Flounders, Moses Wells, William Lobb, and Asher Lobb. In 1846 he bought property from Catherine Lobb and Abraham Rudolph. By 1851 he owned forty-one tenements that he rented to his employees. Between 1853 and his death in 1864, he made additional purchases from William Towne, Nathan Browne, Henry Hay, Samuel Harrison, and John Wall. Dr. Smith, in his 1862 book, mentions that Kellyville extended about one mile up the Darby Creek from Baltimore Pike.

Soon after purchasing the mills, he expanded their capacity and increased the number of workers. In 1826 Kelly’s mill was described as a stone cotton factory, 72 x 42 feet and four stories high containing 30 carding engines of 24 inches, five drawing frames of three double heads each, four double speeders of 20 spindles each, one speeder of ten spindles, one stretcher of 90 spindles, one warping machine and dresser, 32 power looms. 1,260 thresher spindles, 1,776 mule spindles, all producing about 3,300 pounds of cotton per week. It employed about 11 men and 70 women, girls and boys and had houses for sixteen families.

A typical employee worked a twelve hour day, six days weekly and received meager wages. A typical supervisor received $48 per month. A skilled worker received $14 to $18 monthly whereas a laborer received between $6 and $10. Women were usually paid less than the men for similar jobs. It was common for whole families-husband, wife and children – to work in the same mill. The combined year’s earnings of a father, mother and one child amounted to approximately $350. Typical rent for a better tenement house was $25 per year or approximately $2 per month. A typical worker paid $.50 to $1.00 in yearly taxes.

On November 5, 1847, a writer from the Delaware County Republican Paper toured the Kellyville factory and reported this description. He met Charles Kelly who was the superintendent of the Denis & Charles Kelly Mills. “The mill is 160’x 52’, five stories high, clean, well ventilated, a high quality mill of mostly new machinery. The mill is driven by two water wheels 15’ In diameter by 16’ wide, assisted by a high pressure steam engine of fifty horsepower. Two hundred operatives work in the mill, producing 35,000 yards of ticking, flannel, and pantalone per week. They use 40,000 pounds of cotton per month. The workers are happy and contented. There are three other buildings plus a Sunday School, fifty dwellings for workers and others being built. A new 500’ dam is being built. The population of Kellyville is about 500.”

By 1851, Kelly Mills employed 200 people producing ticking, canton flannel, and other cloths. Kelly attracted many Irish Catholics who came to Philadelphia between 1830 and 1850 to escape English persecution and famine. He was able to attract the Irish Catholics from Philadelphia because of their problems that began in the 1830s. Considerable resentment existed between the Protestants and Catholics when the Catholics attempted to use their version of the Bible for their children in public schools. The conflict culminated in the 1844 bloody riots. Some historians believe the riots were more ethnic than religious because the German Catholics were not treated the same. They concluded that the resentment was English Protestants against the Irish.

It was the presence of these Catholics that formed the foundation of Kellyville and necessitated the construction of St. Charles Borromeo Catholic Church in 1849. Having attracted the Irish Catholics to the Kellyville area, a need arose for a place to worship. Originally, a mission priest from St. Denis’ Church visited the Kellyville/ Oakview area, monthly, to conduct services. Kelly donated the ground and stone and helped finance construction of the church. It was one of eleven new parishes begun between 1845 and 1850 by Bishop Kenrick. then Archbishop of Philadelphia. The cornerstone for the first St. Charles church

Kellyville/Oakview

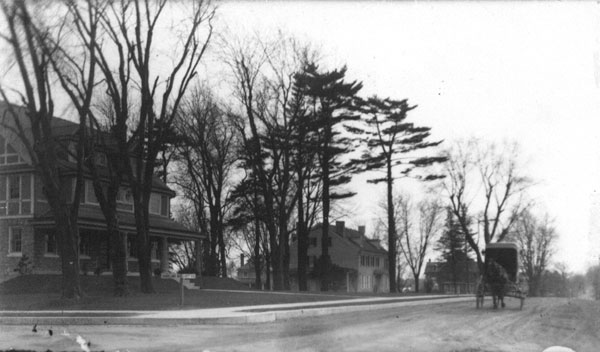

What was once called Kellyville Station on the West Chester and Philadelphia Railroad is now called Gladstone Manor Station. Burmont Road continued across Baltimore Pike and then up the hill to the station. Kellyville had its own post office that later became the Clifton Heights post office.

The area of Kellyville/Oakview was well on its way toward development by 1826. Although Kelly must be recognized as a significant developer in the area, other credits are justified. In the area of Oakview, Thomas Garrett rented a cotton factory to John Mitchell in 1826. It employed twenty-four people and had tenements for five families. Nearby, Garrett also owned a tilt mill, and a mill that made linseed oil. Some of the people living in the Oakview area worked in the Levis Mills situated a short distance up the Darby Creek. When Charles Kelly rented the Lobb mill in 1826, thirty-seven tenement homes already existed in the area. Early maps (1848) of the township show Kellyville as a distinct village. By 1851 Kellyville had forty-one tenements and Oakview twenty-six. The population of the two areas was approximately 500.

Although Kelly was responsible for the early growth of the area, Thomas Kent probably deserves more credit for the perpetuity of both Kellyville and Oakview. People living in the area today are more beholding to Kent then to Kelly.

Thomas Kent

Thomas Kent was born in Middleton, Lancashire, England in 1813. He learned the textile business early in life, became a weaver in a cotton mill, and a foreman by age sixteen. When he left England he was working as a silk weaver, a most complicated form of weaving. His sister, Sarah, who preceded him to America, became the wife of James Wilde, a textile manufacturer on the Darby Creek.

Kent came to America in 1839. He rented a mill in the Oakview area from Thomas Garrett but it washed away in the 1843 flood. In 1845 he purchased the Rockbourne Mill from Edward Garrett, the Union Mill from James Wilde, a linseed oil mill from the Garretts and the Eckstein paper mill. Kent enlarged the mills, converted them to manufacture woolen cloth and later became a major supplier of cloth for Civil War uniforms. Most of the old mills were replaced by new mills in 1867. Two hundred people were working in the combined Kent Mills by the year 1884.

Thomas Kent was a member of the Swedenborgian Church. He was married to Fanny Leonard of Massachusetts whose ancestors came to the colonies aboard the Mayflower in 1620. When he died in Clifton Heights in October 1887, he owned most of the land and houses in the St. Charles vicinity and much of the Clifton Heights area that previously belonged to Kelly.

One of Thomas Kent’s homes, built in 1812, still stands at 3921 Dennison Avenue. Henry Thomas Kent, born In 1854, one of several Kent children of Thomas and Fanny, took control of the mills upon the death of his father. Henry was a Cornell University graduate, a shrewd businessman and the one responsible for the lasting growth of the Thomas Kent Manufacturing Company. In 1900 he sold most of the Kent property, exclusive of the Kent Mills, to Hannah K. Schoff who paid $11,000 for five large parcels of land and all the houses thereon. Henry Kent was one of the organizers of the First National Bank of Clifton Heights in 1902 and participated in many local and national societies. When he died in 1918, his son, Everett L. Kent, born in 1889, became president.

In 1900 and 1910 additional mills named Runnymede, for the area in England where the Magna Charta was signed by King John, were added and used to spin worsted yarns. Kent Mills remained in business long after the other Darby Creek mills. They supplied uniform cloth to the government during the Mexican War, Civil War, Spanish- American War, World Wars I and II, and the Korean War. The January 28, 1943 issue of the Clifton Heights News commemorated the 100th anniversary of the mills. That year Russell L. Kent was the Assistant Treasurer, and 800 people were employed by the corporation, and nearly all lived within five miles of the mills. The mills remained in operation until around 1955. Around the mills grew the village of Kellyville/Oakview, on some old maps identified as Oak Hill.

In the later part of the nineteenth century. attempts to further develop the area progressed slowly. A plan to develop the north side of the 3800 and 3900 blocks of Mary and James Streets and the north side of the 3800 block of Dennison Avenue was submitted to the Planning Board in 1871. A plan to develop the area surrounded by Dennison, Bridge, Mary and Burmont was submitted in 1872 by Hannah Schoff. According to an 1875 Everts & Stewart Atlas, by 1875 only the houses on James and Dennison Streets and some on Creek Road were built. Between 1875 and 1892, two houses and a school were built in the 3800 block of Mary Street. Additionally, the row houses on Blanchard Road were built and other houses were added to the north side of Dennison, then called Church Road. In 1872 a plan to develop the block surrounded by Dennison Avenue, Burmont Road, Mary Street and St. Charles Street was submitted. The 3800, block south side of Dennison plan was submitted in 1921.

At the turn of this century, some of the people, living in the area worked in these nearby mills: Tuscarora, Shoddy, Caledonia, Glenwood, Heyville, Keystone, Clifton Yarn Works, and Modac Mills. Other industry in the area include the Thompson Buggy Works, Shee and Beatty Brick Works, Jones and SheeCoal yards, and the Primos Chemical Works. It was truly an industrial area.

Although most of Kellyville has been redeveloped commercially, Oakview still stands as a well-kept residential area containing many of the township’s oldest homes commingled with post-World War II homes. It is Upper Darby’s oldest hamlet with its origin traceable to at least 1826.

Addingham

On a 1870 map the area was called Heyville, named for Moses Hey who owned a large tract of land in Springfield just opposite Bloomfield Avenue west of the Darby Creek. On this land, Moses Hey owned a textile mill and most of his employees lived in the surrounding village. That 1870 map shows several homes already in the area. About 1900, the village became known as Addingham.

Moses Hey

George Burnley

George Burnley (1804-1864) was born in Littletown, near Leeds of Yorkshire, England in 1804.After learning the textile business he came to America in 1825 and settled in Montgomery County where he operated an unsuccessful carpet business. He moved to Haverford where for a short lime he rented a cotton mill. In 1844 he purchased the ruins of the Palmer & Marker Paper Mill. In 1845 he built the Tuscarora Mills on the site of the mined Palmer & Marker Paper Mills. Tradition is that he named the mills after the ship that brought him to the United States. He became wealthy manufacturing cotton goods and yarn. In 1851, he built the Burnley mansion still standing beneath and south of the Bishop Avenue bridge. George Burnley employed many people and owned several tenement houses that led to the growth of Addingham. He retired in 1861, leaving the business to his brothers John and Charles and son George E. Burnley. George Burnley died in 1864. He was a member of the Swedenborgian Church, married Hannah Lomas in 1838, and had ten children. Among the children, were George E. Burnley (1840-1910), who became a farmer after selling the mills, and Michael (1859-1914) who was a dairy farmer. The family operated the mills until 1870 then sold them to Henry Taylor and John Haley. The mills failed and were sold in 1884 to Nelson Kershaw who Incorporated them into his Glenwood Mills.

George E. Burnley’s home still stands at the corner of Garrett Road and Burnley Avenue. George E. was active in local politics and for several years was a member of the school board. Michael Burnley’s home stood at Morgan Avenue and Garrett Road and some of the farm is now occupied by Garrettford School. Michael sold the property to the school system which built the school in 1909. In 1976, Upper Darby purchased the Burnley mansion, two nearby mill houses and eleven acres along the Darby Creek for $125,000. The homes, near which at one time stood clusters of mill homes, were rented to people who agreed to restore and maintain the houses.

Wilde Family

Nelson Kershaw

Nelson Kershaw (1857-1939) was born in Bradford, England and migrated to America in 1860 with his father John and mother Ruth Pickard. Both parents are buried in Calvary Cemetery in Rockdale, Aston Township. Nelson was naturalized in 1880 along with a brother John. His father was a weaver who worked in the Rockdale textile mills.

In the 1880s, Nelson already owned the Glenwood Mills located near today’s intersection of Palmer Mill Road and Sycamore Avenue and when the Tuscarora Mills became available he absorbed them into his company. He became wealthy producing toweling material. Kershaw owned sixty-five acres of land that later were developed as part of Westbrook Park. In 1905 he purchased twenty-five acres and a beautiful mansion still standing where Palmer Mill Road meets Sycamore Avenue. Additionally he owned several mill houses that stood on Sycamore Avenue until they were demolished in 1986. One mill house, substantially modified, still stands on the corner. An unrelated Kershaw family has lived in it since 1900, when they worked for Nelson Kershaw. In the early l920s Kershaw Mills employed around 200 people.

The 1929 financial crash and subsequent depression severely damaged Nelson Kershaw. The Kershaw mills produced MAR towels for many years until 1934. Then it became impossible to compete with the cheap labor market of the southern textile mills. Kershaw declared bankruptcy and closed his mills in 1934. They never opened again and after years of deterioration they were demolished in the 1940s.

Kershaw was active in Township politics, having served on the Board of Commissioners for fifteen years, five as its President. He was Superintendent of Schools, a Vice-President of the First National Bank of Clifton Heights. Director of the Lansdowne National Bank, a member of the Masonic Lodge and the Manufacturers Club of Philadelphia. He was married to Christina Bennett and they had three children: Lillian, Nelson Jr.,and Edward. Kershaw died in 1939 at his son’s home at 433 Burmont Road and is buried in Arlington Cemetery in Drexel Hill. Dr. James Dunn, who purchased the mansion house in 1936, believed that portions of this house were built by the Levis family in 1720. The Township purchased the original Kershaw Mill area and converted it into a playground.

Many houses standing today in the Addingham area were built in the 1880-1900 period. A few are older. Many original residents were mill workers who migrated from the Philadelphia textile areas. Several of today’s residents are related to each other and to the original residents of the area. Crawfords still live on Bloomfield Avenue where their family operated the M. S. Crawford Dairy until it went out of business in 1962. The Crawford family moved to 531 Bloomfield Ave. in 1921. That house is believed to be more than 200 years old and the oldest home remaining on Bloomfield Avenue. Mrs. Salzman, still living on Bloomfield Avenue, had two grandfathers— Henry Taylor and John S. Henderson. Henderson was a Civil War navy veteran who lived in the area until he died early in this century. About 1882, Henry Taylor built a row of mill houses off Bloomfield Avenue called Henderson Row. The house that Mrs. Salzman lives in today, 515 Bloomfield Avenue, was built by Henry Taylor between 1860 and 1865.

Martha Platt was the area’s midwife and delivered hundreds of area babies. Dr. Nicholas of Clifton Heights was the local family physician.

Bloomfield Avenue, the heart of Addingham, was so named because it led to a large farm called Bloomfield, now Drexelbrook Apartments, that was owned by Nathan Garrett. This farm belonged to several generations of the Garrett family and the original homestead was built in 1771. Before Drexelbrook it was the Aronimink Country Club and later the Hi-Top Country Club and sometimes called Delaware County Country Club. The Clubhouse, built in 1807, was originally Nathan Garrett’s home.

Garrett was a charter member of the Upper Darby Building and Loan Association, a corporation formed in 1868. That year Garrett purchased from his cousin’s husband, George B. Allen, a large tract of land just South of the Bloomfield Farm. That tract was bounded by Darby Creek, Bloomfield Avenue (the upper part), Childs Avenue and Huey Avenue. In 1877 Nathan Garrett submitted his plan to the County Development Board proposing to develop this area. The proposal included subdividing the area into 142 lots, mostly 40 X 120 feet. It contained Upper Darby’s first systematic, perpendicular layout of proposed streets but its development was slow. Although the lots were sold quickly, only nine houses were built in the Bloomfield Tract by 1892. By 1900 approximately 200 people lived in all of Addingham including the Bloomfield Tract.

In the l920’s, Anne Culver was the postmistress of Addingham and her house, the Burnley Mansion, was the post office. Before the Garrettford School was built in 1909 the children of Addingham attended the Central School, built in 1838 and still standing at Burmont Road and School Lane. The Bishop Avenue bridge was built in 1958, but before its construction, Garrett Road turned at Burnley Lane and then ran down Rosemont Avenue to a covered bridge that crossed the Darby Creek. Nearby stood Beaver Springs, a place where people came to purchase bottled water or fill their own jugs. Near the covered bridge stood a row of mill houses called Haigh Row. Another row of old mill houses, demolished in 1956, stood near the Rosemont Avenue bridge. Lillian Palmer, granddaughter of Nelson Kershaw, remembers this row of houses. Her mother, Emma Chadwick was born in this row and her mother’s sister-in-law, Minnie Chadwick, lived in one of the houses.

Today, Addingham remains a picturesque village much as it was eighty years ago when artists and film crews recorded its beauty. Mill remains are scarce.

Garrettford

Garrettford, once called Garrett’s Ford, is a community that developed around the cross roads of Burmont and Garrett Roads. Not much has been documented to describe its origin. In the early 1800s, part of the area belonged to Thomas Garrett and then to his son, William Garrett. It was part of their Thornfield Estate on which they built a tannery near today’s Edmonds Avenue. The tannery was built in 1766, used until 1890, then demolished about 1900. Unlike Kellyville and Addingham, this mill did not contribute significantly to the development of Garrettford.

Burmont Road below Garrett Road was once called Kellyville Road. In the mid-1800s it was a major supply road for mail and products that arrived at the Kellyville Station of the West Chester & Philadelphia Railroad. The road above Garrett Road, laid out in 1715, was built to give the Worrell Mills in Springfield access to the Darby/Haverford Road. Both Garrett and Burmont Roads are among the oldest roads in the Township. Where they cross became a convenient location for small businesses that were accessible to residents living in all directions. An 1848 map shows that several shops were clustered about the Intersection. In 1880 there were at least a country store, shoemaker, barber, druggist, hardware store, blacksmith, wheelwright, baker, candy store, bar, and post office in the area.

Some people believe that the name Garrettford related to a “ford” across the Darby Creek just south of today’s Bishop Avenue bridge. Tradition is that this ford connected the properties of two friends William Garrett and Samuel Levis. This is difficult to believe since Garrettford is nearly a mile from Darby Creek. An 1848 map shows a substantial creek crossing Burmont Road directly in front of the tannery, following the path of today’s trolley tracks. Traveling north from Kellyville one had to “ford” the creek to reach Garrett Road. Maybe this was the “ford” from which Garrettford derived. The creek, now underground, passed through Garrett’s land.

The area originally belonged to Michael Blunston in 1682. It was part of 303 acres that stretched from today’s Lansdowne Avenue to Darby Creek and from Garrett Road to Marshall Road. It was sold to John Davis in 1736 and then to Samuel Levis in 1737. In 1743, it was partially divided when a large portion was sold to William Garrett, a brother-in-law of Michael Blunston. By 1848 the area east of Burmont Road belonged to William Garrett whereas the area west of Burmont Road belonged to J. M. Marker. William Garrett Jr. sold the property in 1868 to George Garrett, Jr. and shortly after that George laid out a systematic perpendicular arrangement of streets and properties. Edmonds Avenue, then called Market Street, was added as were Randolph, McCoy, and Jones Streets. The development plans also included Sloan Street and Marshall Road between Burmont Road and Sloan Street.

By 1875 the Garrett’s had divided and sold most of their holdings south of Garrett Road. However, Ann Garrett still owned two homes on Burmont Road. In 1875 there were at least twenty-five homes and stores along Burmont Road, Edmonds Avenue, and Garrett Road. Between 1875 and 1892, houses were added in the 300 block of Edmonds, the 3400 block of Randolph and Clark Streets and on the 3400 block of Marshall Road. The area of Valley Green Drive was occupied by the Verner hot houses until 1965.

Before the Garrettford School was built in 1909, the young children attended Central School. Garrettford School originally had only nine classrooms and one of its teachers and later principal was Miss Elizabeth Kirk.

The Garrettford-Drexel Hill Fire Company was organized as the Garrettford Fire Company on January 25, 1907 and it was Upper Darby’s first fire company. It was housed in a wooden building that previously belonged to Upper Darby’s first Baptist congregation. The Baptists built their first stone church in 1909 near Edmonds Avenue and Garrett Road, today the Church of the Brethren. The present firehouse, on the same site, was dedicated October 12, 1929, and cost $45,000 to construct.

Cardington

Cardington is along Cobbs Creek adjacent to West Philadelphia, in the vicinity of Marshall Road. Although it contained several mills, it was slow to develop as a residential area because many workers lived in Blockley, now West Philadelphia.

The area originally belonged to Samuel Sellers and John Marshall. John Marshall owned a saw mill that was converted by his grandson, Thomas, to a fulling mill in 1762. Another grandson John, operated a grist mill in the same vicinity until 1776. The Marshall homestead stood for nearly 160 years near where Powell Lane meets Marshall Road. In 1723, Marshall petitioned the court to construct a road from his home to his mills. Marshall Road was one of the earliest roads into West Philadelphia where it connected to Gray’s Lane. Gray’s Lane ran from Haverford Road to Gray’s Ferry, sometime referred to as the lower ferry.

In Cardington, John Sellers (1728-1804) owned a grist mill in 1757, and in 1798 he built what is alleged to have been the first cotton mill in Delaware County. His descendants added grist, saw, paper and cotton mills. Coleman Sellers (1781-1834) built a foundry and machine shop in 1828 that was named the Cardington Iron Works and Sellers Locomotive Works.

Several generations of the Sellers were wire weavers, a trade they monopolized for many years. They invented wire “cards,” used in textile mills to comb fibers into alignment so that they could be woven or spun. It was in the Cardington Iron Works that Coleman Sellers made the “cards” and other equipment for the textile, paper and locomotive industry. The Sellers Locomotive Works made several locomotives for the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad, later known as the Pennsylvania Railroad and now part of Conrail. This plant built the “America,” one of the first locomotives. Although the plant discontinued making locomotives, it continued to manufacture parts for other locomotive manufacturers.

Bankruptcy hit the Cardington Iron Works/Sellers Locomotive Works in 1838. They were purchased by John Wiltbank who rented the mills to Nathan Baker in 1842, who converted them to produce cotton cloth. Joseph Whiteley bought the mills in 1865 then sold them to James Wolfenden, Jr. and Jesse Shore in 1881. In 1852, Wolfenden & Shore were renting other nearby mills that they purchased in 1863.

Although the Sellers family gave Cardington its name, it was the Whiteley brothers and the Wolfenden family that contributed most to its growth. Whereas, the 1826 Report of Delaware County on the subject of manufacturers listed tenement houses for the mills in Kellyville, none were listed associated with the Sellers mills on Cobbs Creek. However, an 1848 map reveals that Church Lane ran to Marshall Road and on both sides of Church Lane there were eight houses. Just above Church Lane, North of Marshall Road, there were three additional homes. The 1851 tax records reveal that less than ten tenants lived in Cardington. In 1872, the number had increased to sixty- four, due mainly to the tenement homes built by Whitely and then Wolfenden & Shore. In 1875, besides the tenement houses, there where several single houses along Marshall Road and a few on Powell Lane and Church Lane. In June 1891, Jonathan and James Wolfenden submitted their development plan of Cardington. In the early 1900’s, there were three rows of tenement houses. One was called “12 gun row” and the other “Whiskey Row.” One row is still standing on old Marshall Road, coming down the hill where the original Marshall Road bridge crossed Cobbs Creek. By 1900, approximately 400 people were living in the Cardington area, but aside from Marshall Road and Church Lane, the area was still undeveloped.

The influence of the Sellers family is forgotten. The “old timers” living “around the Creek” remember the mills of Wolfenden & Shore, that employed 250 people in 1881. The mills made cloth for World War I uniforms and civilian suits and overcoats. Most of its cloth was made from reprocessed carpets that the mill cut-up and processed into woolen yarns. Mr. Arthur (Pops) Jackson remembers having worked in the mills in 1923 when he was sixteen years old. As a boy he made $6 a week. A top weaver in those days made about $25 per week from which he paid Wolfenden & Shore about $1.25 per week rent for a tenement house.

Wolfenden and Shore began in 1852 and closed in 1928. At its peak, it employed nearly 500 people. When it closed, 225 people were still employed. In 1928, the Evening Bulletin reported the closing of the mills after seventy-six years. It also reported that the mills and twenty acres were sold to the Fairmount Park Commission for $1.1 million. A subsequent taxpayers’ suit, denied in the court, claimed that Philadelphia paid more than $30 per acre for property valued at $2,500/acre. In 1930, the Commission demolished the mills.

By 1892, Jonathan (John) and James Wolfenden owned most of the Cardington area including two rows of tenement houses and fifteen single homes. In various generations, the Wolfenden’s lived in at least three mansions, none standing today. One stood behind the present super market and playground on 69th Street. The other stood at Powell Lane on Marshall Road and was demolished when Marshall Road was widened. The third was bought by the Zappasodi family and was sold to the St. Demetrios Greek Orthodox Church and is now the location of their parking lot. In 1926, David H. Wolfenden, born in 1891, was the Vice President of the Wolfenden & Shore Company. His hobby was organizing a nationally successful soccer team in the Cardington area. Several members of the team were hired by the Company to play soccer, many professional soccer players came from Cardington. David’s brother, James, born 1889, was the President of the Company. He was a director for several banks and also interested in the soccer team. Daniel R. Muff, Jr., a descendant of James Wolfenden, Jr., lives at 241 Powell Lane in a home that was built in 1826, probably by the Sellers Family.

The Wolfenden family was active in Upper Darby civic and political activities. James Wolfenden III was a commissioner in Upper Darby and for twenty years (1928-1948) he was a member of the United States House of Representatives. His mother, Pherenna, was an original major contributor to the Delaware County Memorial Hospital.

Cardington had its own school located at Harrison and Watkins Avenues. It was originally a one- story school built in 1922. Later two additional floors were added before it was demolished. Cardington Fire House, Engine #4, was originally built in 1916. Today there is a memorial in front of the firehouse and it includes a large bell taken from the Burd Orphan Asylum when it was demolished in 1930. Excluding the houses along Church Lane and a few on Watkins Avenue, most of the houses were built early in this century by developer Louis Zell. A plan to develop the 400 block of Kent Road and the 6800 of Montgomery Avenue was submitted to the Planning Board In 1923.

Like so many other mill areas, the community was a clannish one where several generations of the same family lived, died and were buried. Many former residents of the area are buried in the nearby Southwestern Burial Grounds. Although the cemetery belongs to the Central Philadelphia Monthly Meeting of Friends, there is an area containing the remains of non- Friends.

The mills are gone, but there are remnants of the Western Ice Company plant built around 1920. On top of its roof stood a large sign that read “ ICE NEVER FAILS.” When the mills closed, many workers went to work for the Kent Mills but continued to live in Cardington. Not far from Cardington stood the Millbourne Mills, owned for many years by the Sellers family. Many of its employees lived in Cardington. This mill operated until 1926 when it was razed to make room for the now vacant Sears, Roebuck store.

Looking back, it is difficult to believe that Upper Darby was at one time a major textile center. That industry and other mills along the creeks, were the basis for the development of the four hamlets little villages. Aside from the hamlets, the remaining areas continued to be mostly farms, orchards, large estates and dairies until the beginning of the 20th century.